The story of two brothers, Lincoln and Booth, in the play Topdog/Underdog by Suzan-Lori Parks is a tale of sibling rivalry, racial and class disparities, family ties, and masculinity. Lincoln, a former street hustler, now spends his days impersonating Abraham Lincoln at an arcade, while Booth seeks to learn the tricks of the trade from his older brother. The play delves into the complexities of these characters, showcasing their individual struggles and the dynamics of their relationship.

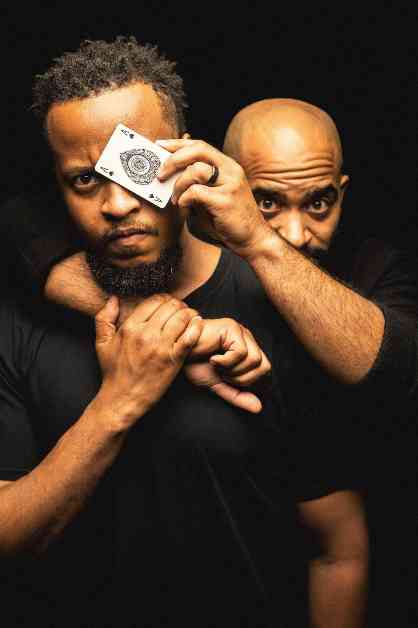

Gregory Fenner’s portrayal of the charming Booth is a marvel, highlighting the character’s hotheaded yet endearing nature. Fenner’s performance is a testament to his exceptional character work, bringing depth and authenticity to the role. Martel Manning’s interpretation of Lincoln as the older, stoic brother is equally captivating. Manning’s portrayal captures the essence of Lincoln’s complexity, drawing parallels between the character and the historical figure he impersonates.

Directed by Shanésia Davis, the Gift Theatre’s production of Topdog/Underdog is a captivating experience that delves into the heart of the story. The chemistry between Fenner and Manning on stage is palpable, adding another layer of depth to the narrative. The play challenges the audience to see beyond the facades of these characters and explore the humanity that lies within them.

As the story unfolds, the audience is taken on a journey of self-discovery and introspection, as the brothers navigate their tumultuous relationship and confront their own demons. Through Parks’s poignant writing and the actors’ compelling performances, Topdog/Underdog invites viewers to reflect on themes of identity, history, and the ties that bind us together.

Overall, Topdog/Underdog is a powerful exploration of brotherhood, ambition, and the struggle for self-realization. The play’s resonant themes and nuanced characters make it a must-see production that will leave a lasting impact on all who experience it. The Gift Theatre’s rendition of this Pulitzer Prize-winning play is a testament to the enduring relevance of Suzan-Lori Parks’s work and a testament to the talent of the actors who bring it to life on stage.